Now that we've gone through the technicals, let's talk about the real elephant in the room: the criticisms and concerns in adapting this particular movie in 2022.

I have seen many reviews so far (here's a link to one in particular) that are very concerned with clarifying for their readers that the musical is a fresh new take on a problematic classic, and that they are doing their own thing that is different (read: better). This comes on the heels of major anti-trans activity across the world, and with the genuine concerns about producing yet another man-in-a-dress comedy (Mrs. Doubtfire being the previous questionable choice) while the queer community is actively trying to combat this particular conservative scaremongering tactic. It is understandable to be concerned, but unwarranted in this case. To say that this new musical is doing something completely different and fresh with source material that should have been kept on the shelf is unfair assessment that both undersells the quality of this particular adaptation and completely misunderstands the original film–a film which was itself radically queer in 1959.

So let's actually talk about Some Like it Hot, the Billy Wilder film. Spoiler warning from this point forward, because we're going to get into it.

Some Like it Hot has often been credited as being the nail in the coffin for the Hayes Code, a set of deeply conservative industry guidelines in place from 1934 - 1968. The Code prevented films from portraying a wide variety of presumed illicit content, such as: drug use, swearing, interracial couples, "white slavery" (but notably not Black slavery), female sexuality and homosexual content. In 1952, the Supreme Court overruled the Hayes Code and removed its legal backing; but in 1959, Some Like it Hot became a box office hit without the Hayes Code seal of approval, and the Code breathed its last dying breath.

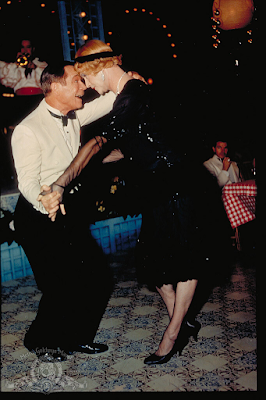

So what makes Some Like it Hot so special? For one, Marilyn Monroe (along with the other girls in the band) are living showgirls who drink, smoke, show off some leg and have sexual appetites. More importantly for this conversation though, Some Like it Hot tangoes with homosexuality and gender diversity with such a thin veil of propriety that it may as well be a cut scene to a train going through a tunnel. I won't go into a full analysis of the queerness of this film here (watch this space for a future blog post that will do just that), but it is important to know that Some Like it Hot is an important work in the queer cinema canon, even though (as far as we know) everyone involved in the making was straight and cis.

But why is this? Why is this film NOT actually a standard man-in-a-dress comedy, even though it is a major landmark in that particular genre?

The big concern with man-in-a-dress comedies is that they are very often based on the premise that, in order to win the girl, these men need to deceive women by pretending to be a woman, thus gaining their trust through deceit. In the end, they always defrock and return to their masculine lives. This is the dangerous premise that fires up anti-trans scaremongering. Mrs. Doubtfire, while a classic film starring a beloved actor, is a prime example of this premise. You could also look to films like Silence of the Lambs or Psycho, in which the trope is then "man dresses as a woman for the purpose of doing harm or enacting a patriarchal victory." These are dangerous stories that do more harm than good in 2022.

Neither of these are the premise of Some Like it Hot.

Rather than being a "man dresses up as a woman to get the girl" story, Some Like it Hot is a situational comedy in which two men end up in unusual circumstances to save their own skins (dressing as women to escape the mob), and come out the other end as fundamentally different people. The man-in-a-dress aspect of this premise is a catalyst towards that change (not dissimilar to the premise of Kinky Boots), rather than a tool towards victory. In the case of Joe/Josephine (played by Tony Curtis in the film and by Christian Borle in the musical), the romance with Sugar (Marilyn Monroe/Adrianna Hicks) isn't fostered or encouraged by the lie of being Josephine but hindered by it, and most of his flirting is done in a secondary male disguise as Junior, the millionaire heir to Shell Oil. Josephine is not after Sugar, and Sugar isn't fooled into loving Josephine, but Junior. By the end of the story, Joe realizes that he's been a scoundrel, and thinks Sugar deserves better than him.

I know what you're thinking. How is that substantially different? How does that make Some Like it Hot a queer film? The answer is...it doesn't. If Some Like it Hot were just about Joe then it would belong on the shelf with the rest, even if drag-aspect isn't in itself the manipulative act. Joe isn't the star of this film, and neither is Marilyn Monroe. The star of this film is Jack Lemmon as Jerry/Daphne (played by the magnificent J. Harrison Ghee in the musical). In the film, Jerry does actually start off as a presumed-straight man ogling and attempting to seduce the women with whom he suddenly has access (an element of the character that the musical wisely omits). It is midway through the film when all of this changes. When Jerry (dressed as Daphne) himself begins to catch the interest of another man, Jerry and Daphne begin to bleed together. Through a series of deeply queer encounters with Osgood, Jerry's previous bad behaviour becomes itself a farce through the actualization of Daphne. Jerry's sexuality and his gender identity are thrown into question. This Twelfth-Night-esque escapade of gender confusion and sexuality awareness is what makes Some Like it Hot a foundational queer film, and what threw the Hayes Code under the bus. It is Jerry/Daphne and Osgood who keep this film fresh and the subject relevant. Some Like it Hot is, at its core, a comedy about change and becoming a better version of yourself.

But you didn't come here for a history lesson about Some Like it Hot, you came here for a review of the new musical, so let's come back around to adaptation, and the brilliance of this one.

Adaptation is a difficult business. When you make an adaptation, you at once need to both be referential to the original source material and make it uniquely yours. Adaptations that stray too far away from the original source material will attract the ire of fans and will very often (though not always) miss the elements that make the original great in the first place. Adaptations that stick too close to the original either suffer from not adjusting to their new medium (a film and a book do not tell stories in the same way) or fail to stand out as significant works of art in their own right. The reason I take issue with the critique that this new Some Like it Hot musical is a completely new take on a classic is because that statement is a disservice to the skill behind this adaptation.

I was excited when I sat down in the theater, but also quite nervous. I love Some Like it Hot, and there is very little that I would change about it. I was worried that this musical wouldn't live up to its source material. My worries were unfounded, and I walked out of the theater grinning from ear to ear, buzzing to see it again. What makes this adaptation sing is that it has masterfully balanced being the same story, but making it unique and fresh for a 2022 audience. It is truly an update that gives the story more depth. One of the greatest sins of adaptation is, in my opinion, the red pen. It is infinitely tempting to correct, edit, and change the things you don't like about a story to make it fit your vision of how the story should be. While there were a few corrections (such as dropping Jerry's hound dog approach in the first half of the story), I don't believe that the creators of this musical took a red pen to the story. Rather, I would say that they took a "Yes, And" approach. Every change that was made to the story served to give the characters more depth rather than change the characters themselves. Yes, this is the character, And here's a little bit more to make them richer for it.

Making Daphne/Jerry and Sugar Black instead of white added depth to their circumstances and was a logical refresh to add diversity to a story about jazz musicians. More depth was added to Sugar's story by giving her a Hollywood dream, which brought some justice to Marilyn Monroe's part in the role (Marilyn notably fought back against being just a dumb blonde as Sugar). Making Junior a scriptwriter instead of a random millionaire contributed to this narrative rather than being a somewhat random aside. Every change and addition streamlined the story for the stage and made each character more three-dimensional in the process. To both streamline and add padding is no easy feat, and should be applauded.

In an interview, Christian Borle said their version of Some Like it Hot is still the same story, to which J. Harrison Ghee followed up that it was also uniquely their version of it. Both of these sentiments are true, and that is a difficult thing to achieve. The fact that this balance has been struck makes it a masterwork of adaptation.

Moreover, J. Harrison Ghee's performance is spectacular as Jerry/Daphne. The most substantial refresh to the story is to have this character unabashedly and clearly accept their gender fluidity with a showstopper song and a cheering ovation. When the New Yorker reviewed this show, they referred to this change as "splic[ing] old-school fun with contemporary gender politics". Aside from the somewhat patronizing and obviously click-baity nature of that description (which drew the expected ire from commenters on Twitter), it also is fundamentally untrue. There is nothing uniquely contemporary about Some Like it Hot's gender politics, because Daphne's queerness is intrinsic to the source material. It wasn't created for the musical. What is contemporary and fresh in this case is that we now have the language to express said gender politics with dignity and respect. What this new Some Like it Hot has done is take an already (some might say quietly) queer work that toyed with gender in 1959 and say the quiet part out loud. This is the finest example of a “Yes, And” approach that the musical has to offer. Yes, this is exactly who Jerry/Daphne always was, And now we're going to make that explicitly clear.

This is the Jerry/Daphne that queer viewers of the original film have always loved, now brought to life. I cannot express how grateful I am for the fun and joy in J. Harrison Ghee’s performance. Ghee’s Daphne is genuine and real without losing a single beat of comedic timing. Daphne is the breath of fresh air that we need in this horrible year where we as trans people have been put under constant surveillance. Some Like it Hot allows us to have fun, and we so desperately need it.

Billy Wilder said that 1959 wasn't ready for what happens after the ending, but 2022 is. In 1959, both Jack Lemmon and Joe E. Brown portrayed Daphne and Osgood’s relationship as something fundamentally positive, both playful and sexy. In 2022, we can take what we already had in 1959 to its logical conclusion, and finally allow Daphne that security she wanted so damn badly.

I always think about this movie in terms of its ending. It has the perfect ending, no other movie can compare. Still, I always thought that in a modernization, the only thing to change is for Osgood, instead of delivering a punchline, to just say "you're perfect". The ending of this show is different, and it's not the exact same scene-by-scene play-by-play story, but it is perfect. You really are perfect.